Exquisite cirque acts include an intriguing edge of darkness

By Mel Shields — Bee Correspondent – (Published October 3, 2004

There is an argument that there are too many cirque-style productions in Nevada. That may be true in Las Vegas where, for example, Cirque du Soleil seems to have a stranglehold on Strip production, but Reno has seen only a few.

Now “Taganai” – which means “moon holder” and is a section of the Ural mountains – arrives at the Eldorado and proves there’s always room for one more of anything if that one more is particularly good.

The joy of watching “Taganai” in the Eldorado Theater is the joy of intimacy. This is a European circus experience presented as it should be, allowing a much stronger and more sustained relationship between performers and audiences than could be possible in an arena or giant casino space.

The result is not always pleasant. “Taganai” has a darker feel than many other such shows. The costuming includes soldiers’ winter coats and flapped caps, with targets on the backs of many of the coats. Strange, ghostlike creatures often float across the stage, looking every bit as if they’ve just come from some nuclear reactor where they were insulated against radioactive material – Chernobyl chic. They are as haunting as they are intriguing.

These touches, and many more, provide an undercurrent to the on-stage theatrics. At one minute, the show is celebrating the magic of the human body. At the next, that magic seems very fragile, indeed.

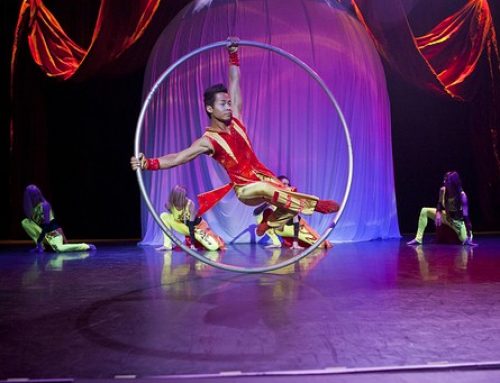

Not that there is little joy; there is a great deal of it. The clowns in “Taganai” are especially good, as are the acrobats, contortionists, jugglers and tumblers.

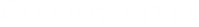

“Taganai” features a cast of 30, and the members are seemingly everywhere, at center stage and in background scenarios as well – standing against revolving doors, moving across the stage in giant rolling doughnuts. Heads pop out of tables, giant balls are rolled across the stage, sabers are waved, a Chinese circus lion appears.

The cast members who take center stage are often breathtakingly good.

For instance, Anait Seyranyan performs a hand-balancing contortionist routine that is one of the most eloquent sustained achievements to be found in any performance art. What she does with her body brings the expected gasps; what she does with her art brings unexpected awe.

She is joined earlier by sister Tatevik as they fold themselves into squares and slide sideways into the same small transparent box.

The only non-European in the cast is Diane Wasnak, who appears as a baby who spots her “Uncle Fwed,” an unsuspecting audience member who finds himself first playing ball, then teaching her how to ride a bicycle, and finally, tossing bowls and spoons to Wasnak as she circles backward on the bike and flips the items from her feet to her head.

Throughout, Wasnak masterfully sustains her comedic character and weaves it with acrobatics.

Ilya Zaripov and Andrey Zarubalov also manage to create memorable clown characters: Zaripov most engaging as an artist creating drawings of members of the audience, and Zarubalov juggling ping-pong balls that pop out of his mouth.

Gagik Seyranyan joins Anaida Akopyan for some limbo feats climaxed by Seyranyan somehow manipulating his body under down-thrust knives and over up-thrust spikes. Julia Smirnova performs lovely feats while balanced on a fellow performer who is balanced on a ladder balanced on a springboard. And Anna Rastsova manages to perform feats on single trapeze that make a catcher or partner superfluous.

There also is a troupe of acrobats who perform singly and in ensemble on parallel bars with such grace and timing that one wonders why such a sport has never been part of international competition.

Kudos to executive producer Mikhail Matorin’s creative team, especially Vasily Bogatyrew, whose music perfectly captures both the show’s light and dark moods and mostly avoids being too cirque-derivative; Dana Perri, whose choreography is always to the point; and the technical crew.